This week I have been continuing my research into typographers, publishers and designers whose work could inform the direction of my project. I have also started to engage with the Phase One lectures, particularly the one on academic writing, which has helped me think about how writing and making can work together within practice.

Phase One Lecture: Academic Creative Practice

This session focused on how writing is not separate from design, but part of the process. Writing clarifies ideas, exposes connections, and shapes enquiry in the same way that making does. The key point was that writing should not only describe but also take a position, linking theory, process and meaning.

A strong research question is central. The best questions are specific, open enough to allow exploration, and achievable within the scope of the project. They build on existing knowledge and add a small but meaningful contribution.

Case studies highlighted how practical experimentation, historical research and critical reflection can sit together in one project. It reinforced the idea that design research is iterative — each stage leads naturally into the next.

Some practical advice that stood out:

- Write critically, not just descriptively.

- Build arguments with evidence rather than relying on opinion.

- Structure is essential, from paragraphs to chapters.

- Be clear and precise, use strong verbs, and avoid jargon.

Ultimately, academic writing was framed as part of creative practice, not a hurdle. Reading, writing and making all feed each other.

Case Studies

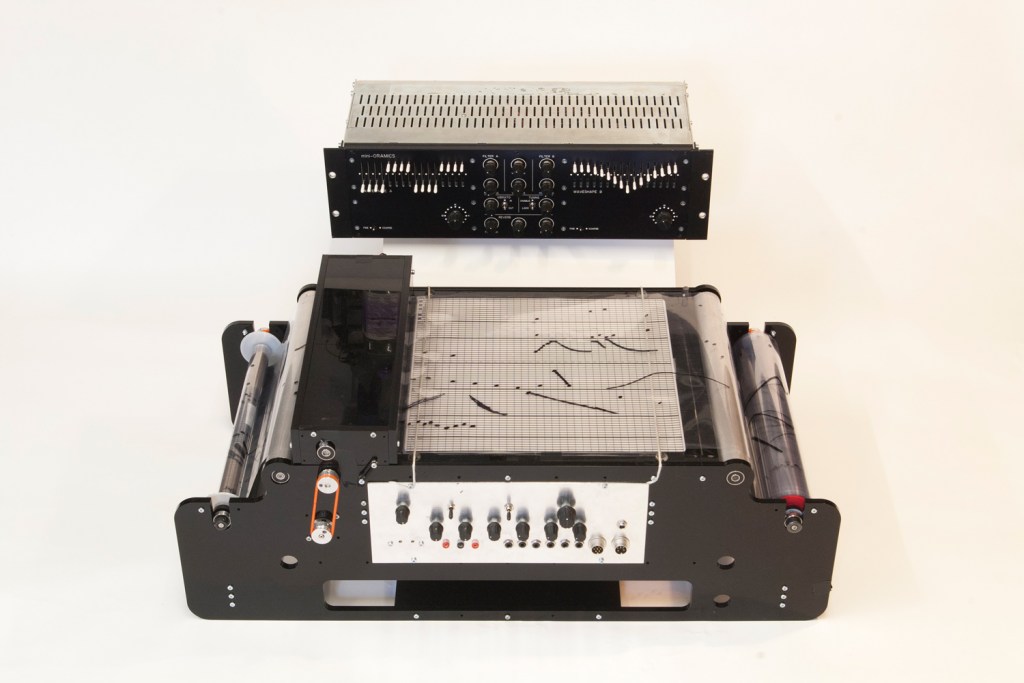

• Mini-Oramics Instrument

A design researcher rebuilt a forgotten musical instrument based on historical designs. This involved practical experimentation, historical research, and critical writing – all connected through a clear methodology. A great example of creative speculation backed up by deep academic enquiry.

• Digital Renders & Gentrification

A photographic researcher explored how digital imagery (like architectural hoardings and renders) shapes how we perceive urban spaces. Her project combined large-scale photography, critical theory, and analysis of media trends. This highlighted how research can inform visually impactful outcomes while being rooted in academic critique.

Reflecting on Practice – Brown’s Questions

After completing a project, it’s helpful to write down key insights while they’re still fresh. These questions can help:

- What did I do?

- Why did I do it?

- What happened?

- What do the results mean in theory?

- What do the results mean in practice?

- What’s the value of this project to others?

- What remains unresolved?

The final question is especially important – it often points to the next stage of research.

Writing Strategies & Styles

• Think Critically, Not Just Descriptively

Academic writing should analyse, not just describe.

Examples:

- Descriptive: “This happened.”

- Critical: “This happened because…” or “This shows that…”

• Build Arguments, Not Opinions

Argument-based writing uses evidence, reasoning, and engagement with counterpoints. Avoid purely personal opinions without justification.

• Structure is Everything

Whether writing a paragraph, chapter, or full dissertation, structure keeps the reader oriented.

Try this process:

- List your main points

- Organise them logically

- Write them into structured paragraphs

Also, make regular use of headings – these guide the reader and reinforce key ideas.

Writer Types

There are two main types of writer:

- Holists: Write everything in one go and edit later (like turning sausages into salami).

- Serialists: Plan everything carefully before writing, editing less.

Both are valid. Whichever style fits, clarity and structure remain key – especially as the word count grows.

Contextual Reviews

Think of the contextual review as the academic equivalent of a design research phase. It maps existing theory, practice, and precedent, identifying where there’s a gap and where your work fits in.

This is where your positionality (where you stand in the debate) becomes visible. You’re not just summarising – you’re showing why your work matters.

Practical Writing Advice

• Be Clear and Precise

Avoid jargon and vague statements. Use precise figures and examples, especially when referring to facts, data, or timelines.

• Use Strong Verbs

Swap generic verbs like “says” or “shows” for more dynamic ones:

- For claims: argues, asserts, insists

- For agreement: acknowledges, supports, endorses

- For disagreement: questions, challenges, critiques

Keep a thesaurus open!

• Maintain Formal Tone

Avoid casual language or spoken phrases. Keep grammar and punctuation sharp – even small errors can undermine the credibility of your writing.

Referencing & Tools

- Always reference correctly – don’t quote anything unless you’re using it to make a point.

- Follow a consistent citation style (usually Harvard).

- Avoid plagiarism at all costs. Use tools like Turnitin and Zotero to help manage references.

Word Count & Focus

Word counts are strict and usually include everything except the bibliography. Don’t try to ‘hide’ words in captions, tables, or footnotes. Stick to the limit and always allow space to refine near the end.

Avoiding Procrastination

Distractions (especially online) are one of the biggest barriers. Set yourself goals, work in blocks of time, and find a routine that suits your energy. Whether it’s early morning or late night, know what helps you get into writing mode.

Final Thoughts

Academic writing is its own language. It takes time to learn, and the best way to improve is by reading academic work – articles, dissertations, critical essays – to get a feel for tone and structure.

Ultimately, the goal is to create better, more thoughtful design work.

“Learn only in order to create.”

Writing isn’t a hurdle. It’s part of the practice – part of what makes us better, more reflective designers.

Week 3 Webinar

The webinar asked what it means to be both a designer and a researcher. It explored how design knowledge differs from scientific knowledge, and how practice can generate cultural, social and sensory understanding.

Several theoretical positions were discussed, from Papanek’s focus on clarity and order to Escobar’s critique of colonial structures in design. The session also stressed the importance of positionality — recognising that personal background, experience and values shape any research journey.

I was reminded that methodology is not one-size-fits-all. Frameworks like the Double Diamond can be useful, but they should be adapted to fit the way I actually work.

My Research Question

After reflecting on my previous units, I have arrived at an initial research question:

Why does the visual representation of dialect matter in an increasingly globalised design culture?

This builds directly on my interest in typography, language and identity. It allows me to examine how dialect has been represented visually in the past, how current design culture responds to it, and what the future possibilities might be.

This feels like the right starting point for my Final Major Project — grounded in my own practice and experiences, but open enough to expand into wider cultural questions.

Leave a comment